Blood in the fields

They were chased from their homes. Hacked in the fields. Thrown into wells. Rural Gujarat had never seen such widespread brutality—and all planned in cold blood..

DIONNE BUNSHA

in rural Gujarat

“Cleanse the village of cow-eaters. Remove all Muslims. Chase them and kill them,” blared over a loudspeaker around three weeks back in Pandharvada village in Panchmahal. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) was holding a public meeting. Local police guards and a district official were present. They sat on the sidelines, drinking tea, laughing and soaking in the atmosphere. Pandharvada’s Muslims stayed out of harm’s way, fearing the worst. Three weeks later, the VHP’s supporters carried out their threat. Around 21 people were killed when the Muslim bastis were burned. The survivors fled. The VHP had achieved its end.

Akhtar Husain Sayyed, who survived the Pandharvada attack, narrates this chilling tale in Godhra, 85 km from his village. He is seeking shelter in a relative’s house here. Two of his family members are still missing. His mother and sister escaped being burned alive. “When we heard about all the violence in the state, we were scared. The local BJP taluka delegate offered several families protection. He locked us inside a room and let the mob set it on fire. They had planned it all,” says his mother, Miriambibi.

The elderly Nathubhai Sheikh saw his two sons hacked to death. When a mob attacked the Muslims in Pandharvada, he ran into the fields and saw his two sons being attacked by people with swords. His third son is still missing. “I hid in the wilderness for a few days, until the military found me and took me to Lunawada relief camp. From there, one of my relatives from Godhra brought me to his house,” he said.

In the violence which followed the burning of a compartment on the Sabarmati Express near Godhra, rural Gujarat has, for the first time, witnessed heinous attacks on Muslims. Throughout Gujarat’s gory history of communal clashes, cities and small towns have had their fair share of communal violence. But rural Gujarat remained untouched. This time, however, since the attacks are part of the Sangh Parivar’s diabolic design, Gujarat’s villages have been included in the saffron ‘cleansing’ process. Most cases of violence were not riots, but well-orchestrated attacks. They did not involve a clash between two communities. It was the systematic hunting out of Muslims.

“We get the feeling that these attacks were planned. Mobs seem to have been systematically rounded up from other villages, instigated and let loose,” says Raju Bhargav, Panchmahal district’s police superintendent. “Some of the people we arrested at the scene of the crime belonged to villages even 15 to 20 km away. It’s the first time that villages are experiencing such communal fury.” The worst affected districts have been Panchmahal (where Godhra is located) and its neighbouring districts -- Dahod, Sabarkantha, Banas Kantha and Mehsana.

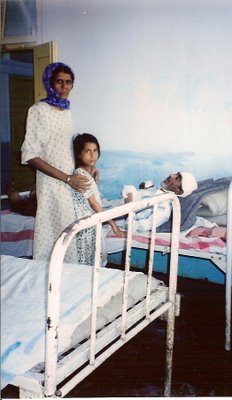

Rural Gujarat has never witnessed such a brutal and calculated witch-hunt. In Pandharvada, nine-year-old Noorunissa was slashed on her back with a sword. Her father, Razak’s two fingers were chopped off and his head injured. “We hid in the jungle for two days. The police came on the third day. By then, I was unconscious,” says Razak who is in Godhra general hospital. Muslims have been chased and killed, their houses and shops burned. Entire bastis have been evacuated after the attacks. The number of missing persons and displaced families are yet to be counted.

Children and women have also been targets. In Anjanva village in Panchmahal, 11 people, died when they were thrown into a well. Four of them were children. Maksooda and Hanif Rahim lost their young children, aged three and two years, in the attack. Along with Maksooda, the infants were thrown into the well by a mob that attacked the village’s Muslim basti. “People came from other villages and started burning our houses. We all ran, but some of us were caught and thrown into the well,” says Maksooda who was the only one rescued from the well by the police. The rest were already dead. She suffered head injuries and is being treated at the Godhra general hospital. They are safe for now, but Hanif and Maksooda have nowhere to go after Maksooda has been discharged from hospital.

In some villages, local Sangh Parivar activists even warned the Muslims of their impending doom. “On the night before the VHP bandh, the sarpanch and RSS chief of the village came to my house and told me that we (Muslims) should leave by morning or there would be trouble,” says Himmat Khan, a resident of Sundarpura village in Mehsana. But the community decided to stay on. “There was a bandh. We were scared there would be trouble outside. When the mob came in the evening and burned our houses, we all ran to our Muslim friends in Sardarpura village nearby. They were also attacked within a few hours,” he says.

Sardarpura witnessed one of the most gory crimes in the recent Gujarat riots when 29 people, many of whom were women and children hiding from the mob, were locked inside a house and burned alive by the Patel (a landowning caste) leaders. Shameem Husain, a 20-year-old lost her mother, two brothers and a sister when the house was set ablaze. “I managed to get out of the burning house and hid in a bathroom,” says Shameem. A farm worker who works for Patel landlords, Shameem and her handicapped father now take refuge in Savala village, 30 km away.

While the former sarpanch (village head), along with several others have been arrested in Sardarpura, many other Sangh Parivar activists still roam scot-free. “We have to be careful while making arrests. If we start arresting many ruling party activists, we will be under pressure,” admits an official. Yet, there are no excuses for the police failure to protect lives and property. “For the past two months, I was threatened by the Bajrang Dal. They wanted me to leave the village,” says a Bori (a trading caste) Muslim trader from Dekva village in Panchmahal. “I was given police protection. After the Godhra incident, our shop was burned. The police inspector was there while it happened, but did nothing. If the police had acted, a lot of lives and property would have been saved.”

Economic interests also underlie the communal agenda. “It’s very simple - our land is very valuable. It is fertile and has borewell irrigation. The Patels want to get hold of it,” says Munsaf Pathan, a large farmer who survived the Sardarpura attack. Muslim shops, occupying prime space, near bus stops or railway stations, have also been targeted. Hindu shops adjacent to them remain untouched. The likelihood of Muslims returning to set up shop is slim. “In the tribal areas of Panchmahal and Sabarkantha, there has been a history of class conflict between Bori Muslim traders and tribals. This has been exploited by the Hindutva brigade who have given it a communal colour,” says activist Rohit Prajapati. In many places, tribals have been instigated to loot. “Bhil tribals in this area are extremely poor. The district has suffered bad drought conditions for the past two years. In some cases, they used this chance purely to loot,” says Raju Bhargav.

Yet, the over-riding motive was communal frenzy, effectively stirred up to fever pitch by the Sangh Parivar. Over the last decade, organisations like the RSS, VHP and Bajrang Dal have managed to make inroads into rural Gujarat. “Though its traditional support is from the trading community, the Parivar has managed to saffronise even OBCs, dalits and tribals since they follow more Hindu customs compared to dalits or adivasis in other states,” says human rights lawyer Girish Patel. The VHP first started mobilising support in Gujarat’s campaign when they started the Rath Yatra campaign in 1990. Its recent Trishul campaign to convert people to Hinduism has also succeeded in inciting fervour. The BJP’s rise to power in the state in 1995 and the use of money-power in deprived areas have also fostered its growth.

The recent attacks were a culmination of their strategy. It seems to have paid off for the VHP. Many Muslim bastis are deserted. People are shattered both emotionally and economically. Muslims have been left with nothing but the clothes on their back. Mission accomplished, the Sangh Parivar still refuses to put away their trishuls and loudspeakers, and forget about cow slaughter. Even after the butchering hundreds of people has been completed.

Frontline Mar. 16 - 29, 2002 Also available here

No comments:

Post a Comment