Red carpet for lions, red card for people

Some of the Gir lions needed another home. The adivasis in Kuno forest gave up theirs on promises of a better life. But were given little more than stony land

DIONNE BUNSHA

in Kuno forest, Madhya Pradesh

Akke and Kheru share a beedi with their friends and stare at the stone in front of them. Blazing heat and rugged terrain is all they have. No trees, no crop, no cattle, no food, just stony land. Nothing can be grown here. All they can do with it is hammer away, breaking rocks for construction. They get just Rs 70 for a 100 huge boulders.

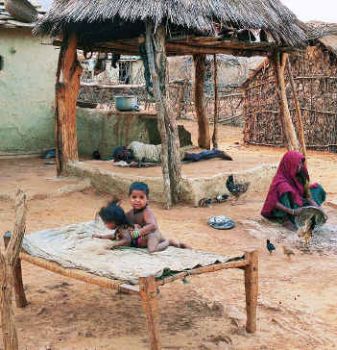

Their village, Pehra, on the outskirts of the Kuno-Palpur forest located in the Vindhya hills in north western Madhya Pradesh, was moved out of the forest six years ago. Around 24 villages, 1,545 families, mainly Sahariya Adivasis, were re-located outside the jungle to create a sanctuary for 5 to 8 Asiatic lions to be translocated from the Gir forest, in Gujarat. Since they were shifted out, it’s been six years of hardship, dire poverty. The lions have yet to be brought into the forest. Meanwhile, thousands in the displaced villages are starving.

In the stark landscape of re-settled Pehra, there isn’t even a tree where Hakke and Kheru can sit in the shade. Just vast stretches of thorny, scrub bushes and the hills in the distance. “This land is useless. Every crop I tried has failed. The soil doesn’t retain any water. The government told us that we would be given fertile, irrigated land with bunding,” Hakke told us. “Forget irrigation, the land is too shallow to hold any water. The crop just dries up or gets washed away.” People who were able to grow two crops in the forest are now reduced to being footloose daily wage labourers, scouting for work everyday, not knowing where the next meal will come from. If there is a next meal.

“Now, our village is empty. There are only 20 families left in a village of more than 100 houses. Many have locked their homes and have left for Sheopur town to cut the harvest in other people’s fields,” said Kheru. “When we lived in the forest, only a few would migrate during the lean season, and it was out of choice. Here, everyone has to keep travelling, searching for work. We didn’t even know how to break stones.” Reminiscing about his old village, he continued, “We could grow two crops without irrigation. At this time, farmers would be selling their harvest. We would swim in the river. Instead, here we are, sweating in the sun, breaking rocks.”

Even when they lived inside the forest, the Adivasis were poor, but life is worse after re-location. “The forest gave us all we needed - milk, ghee, fruits, vegetables, animals, herbs, berries. We got money from selling, tendu leaves, gum etc,” says Munna, from Jakhoda village, who has been suffering with TB for two years. “Here, people don’t even get to eat rotis on some days, so they fall ill. We didn’t need a doctor.” People’s diet reduced drastically. In many of the re-located villages, children are malnourished. One who we came across in Paira died days after we left.

People were moved out with the promise of better facilities, but even water is scarce. “In the forest, we had the river. Here there’s just one hand pump in the village for so many families. There’s no water for baths,” said Kheru. “Cattle can’t survive here because there’s no grazing ground. We had to abandon all our cattle in the forest. Now, if we want to plough the field, we have to hire a tractor and pay an additional Rs 1,800.” With every attempt to sow the land, debts keep accumulating. People borrow to sow the fields, but there is no crop.

After several years of losses, the people of Pipalbawdi village decided to return to the forest for the monsoon crop in 2004. The forest department let them. They knew that the land they were given in the re-located village was barren. “We stayed there for three years, but there was no crop, no work. Here, there is as much fertile land as your heart desires. We don’t need to go anywhere for work,” said Ramdayal. He was part of a large group that gathered round, weary, but eager to speak. “So many years without any crop drained us completely. After many crop failures, people have huge loans to pay off - up to Rs 30,000-40,000, at 60% interest.”

Sabu’s family harvested a mustard crop this year, but all of it went to the bania (trader), paying back a loan. At the end, they were left with nothing. “At least now, we are making up years of losses,” she said. The nearest doctor or bus stand is 9 km away in Agraa village. There’s no transport, people have to walk there. The school inside the forest doesn’t have a teacher. Yet, the people of Pipalbawdi feel they are better off inside. Says a lot about their “Rehabilitation” and the “better facilities” they were promised outside. Besides Pipalbawdi, there are two other villages inside the forest. Still, they are willing to go back to the re-settlement village if they are given suitable land on which they can grow a crop.

A few days after we visited Pipalbawdi, there were reports that forest officials punished and harassed villagers, and pulled them up for not moving back to their re-location site and speaking to journalists. Around 40 men and a few women were reportedly forced into forest department vehicles and taken to their outpost at Pohri, 50 km away, according to Samrakshan, an NGO working in the area. However, Chief Forest Officer, J.S. Chauhan said, “They were asked to come out for their own good. We let them cultivate the rabi (winter) crop inside and now they have nothing to do. If they come out of the forest, we can give them some daily wage work.” He denied that the eviction was prompted by our visit.

Kuno was selected for shifting a pride of Asiatic lions from Gir in Gujarat. Scientists from the WII felt that translocation of some of the expanding population of Gir lions was necessary to preserve the last surviving lions of the species. If an epidemic were to hit the lions in Gir, an entire species could be wiped off the face of the planet. So, a satellite population in Kuno is necessary. That meant declaring 345 sq km of the forest as a sanctuary and re-locating 24 villages outside the forest. Although the villages have been re-located, the Gujarat government refuses to shift the lions, it wants them to remain in Gujarat alone.

The Kuno rehabilitation package offered evicted Adivasis a deal that was supposed to improve the quality of their lives. They would have access to electricity, transport, schools, dispensaries, irrigated land, grazing grounds, firewood plantations and money for house construction. It was “voluntary”, villagers agreed to move. The rehabilitation was considered “successful” by many wildlife conservationists. J.S. Chauhan, then co-ordinating the project, was given the Sanctuary Wildlife Award 2002 for Earth Heroes. Despite a comparatively good rehabilitation package (compared to displaced people in other parts of the country), re-located people are worse off in their new relocation sites.

There are a few who feel they’ve got a good deal. “We have more facilities- electricity, a doctor close at hand, transport. Yes, there are many things promised but not given like fodder and firewood plantations, some irrigation wells haven’t been dug, electricity for pumps. But there are bound to be problems, nothing is perfect,” said Mahesh Mirda, sarpanch of Palpur village. His brother, Suresh, disagreed. “They brought us in the middle of nowhere, where there was one handpump and nothing else and left us to die. What’s the point of running a school if there is one teacher for 250 children? They fooled us and got us out of the forest.”

Village leaders were shown various properties and asked to approve their re-location sites. Then, land was distributed amongst people on a lottery basis. “The powerful people took the land closer to the river, and we were left with stone,” said Ramkali, from Paira. Moreover, when the forest officials showed people the land, they were promised it would be cleared of all bush and made suitable for cultivation. The clearing was done but there was no land or watershed development.

“The entire responsibility of rehabilitation cannot be placed on the forest dept. alone. We don’t have the technical expertise, and need the help of other departments like irrigation, education or health. We have tried to respond to all complaints,” says Chauhan. “For irrigation, we have asked for more funds. It’s not easy to irrigate 3,000 hectares. With the help of other departments, it will take 5 to 6 years. If we have to do it on our own, it could take 15 to 20 years.” Chauhan feels that rehabilitation projects should be undertaken with a different approach. “Yes, the forest dept. should have been more visionary, but why did people agree?”

So, how “voluntary” was the re-settlement? Were people really given a choice between staying in the forest or moving out? Or was it more like a fait accompli? “They wanted us out of the forest so they promised us Rs 1,00,000, but we got only Rs. 38,000 in cash. The government spent the rest of the money to build facilities and clear the land,” said Suresh. “We agreed to come out because they promised us so much money, and assured us that we would get the same kind of land. People have never seen that kind of money, we got greedy and realised later that we had been fooled,” said Hakke.

Now, Kuno jungle is supposedly free from human degradation. Forest officials claim the prey (like deer, chital, wild boar) for lions has increased. The scene is set for the arrival of the Asiatic lion from Gujarat.

At what cost? Was there another, less destructive way possible? “In India, finding a large enough forest for carnivores is difficult because our population density is so high and our forests are degraded and fragemented. After looking at all other alternatives, Kuno was found more suitable. When we spoke to people, they were willing to move,” said Ravi Chellam, lion expert who was part of the WII team that recommended translocation to Kuno. “They can’t remain inside the forest with the lion. That might lead to conflict.”

Yet, with no other alternative, many Adivasis like those in Pipalbawdi, would prefer to break the law rather than break rocks.

Frontline, May 21 - June 3, 2005 Also available here

No comments:

Post a Comment