Free and Unfair Elections in the Wild West

Even as the attacks on the minorities continue relentlessly, the BJP government's priority in Gujarat appears to be holding Assembly elections rather than providing relief and rehabilitation.

DIONNE BUNSHA

in Panchmahal and Vadodara

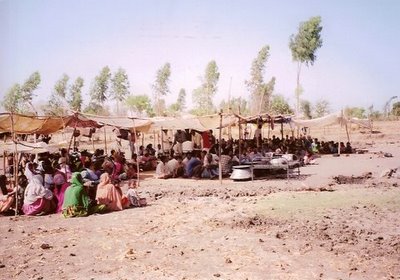

Around 1.5 lakh refugees are stranded in Gujarat’s relief camps. Several people die in violence here everyday adding to the 800-odd killed so far. Chief minister Narendra Modi sat back while VHP, Bajrang Dal and BJP workers orchestrated targeted attacks across the state, killing and hounding Muslims out of their villages and ghettos. The attacks continue relentlessly in Ahmedabad and other parts of north and central Gujarat. Police barge into Muslim houses and harass them as part of ‘combing operations’. Villagers whose homes have been destroyed are living in the open fields. There is no way out for the homeless refugees in relief camps. They cannot return to their homes or start work again.

Yet, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government’s priority during the continuing fascist witch-hunt of Muslims in the state isn’t to restore peace, but to hold elections soon. Its time to grab the spoils of the state-supported Hindutva attacks, to count votes over dead bodies.

Chief minister Narendra Modi sat back while VHP, Bajrang Dal and BJP workers orchestrated targeted attacks across the state, killing and hounding Muslims out of their villages and ghettos. Now, he wants to get refugees back to their homes so that he can get on with the elections. People are being pushed back without providing them any safety or proper rehabilitation. It doesn’t matter whether refugees are ready to return home. The government has to prove that the state is ‘back to normal’. But as long as the Sangh Parivar’s goons roam the streets scot-free, neither peace nor rehabilitation stand a chance.

Local peace meetings organised by the collectorate to get people back to their homes aren’t working out as planned. In some instances, they are re-kindling violence, rather than trust.

Bismillah Khan returned to the Baska relief camp from one such meeting at his village Rameshra in Kalol on April 12th, disappointed that the local leaders didn’t show up. But little did he know then that his house and two others were burned soon after he left the village, as he made his way back to the relief camp that night. His hopes of returning to the village went up in smoke. An unspoken message to stay away. On the night before the next meeting scheduled for April 16th, three more houses were set on fire. Enough to sabotage any sign of peace. “How can we return when the police has done nothing to make sure we are safe, when our houses and shops are totally destroyed?” asks Bismillah.

Others, who have attempted to return, have also run back to the relief camps. Alibhai Rehman Khatri’s Hindu friends from his village, Rawalia, visited him in the Baska relief camp in Halol district and convinced him to return and open up his shop. “I took a loan of Rs 6,000, stocked the shop with supplies and re-opened my shop for eight days,” he says. “Then, there was a Bajrang Dal meeting in a nearby village, where they apparently planned to burn my shop and kill me because I had the guts to return. After that, I haven’t gone back, even though my Hindu friends support me. They could also be targeted for helping me.”

In many places, even police escorts haven’t helped. The police took Pathan Jafar Khan back to his home in Baranpura, Baroda to assess the damage. “While they were filing the report, a huge mob attacked from all sides. The policemen ran. Those in the Special Reserve Police tent stationed there refused to come out and help,” says Pathan, who is still seeking shelter in Baroda’s Queresh Jamatkhana relief camp. Mehboob Sheikh from Kanvat village may also have a long wait in the relief camp. “The police came back after assessing our home in the village and told us that it wasn’t safe for us to go back,” he said.

Even though relief camps are the only refuge, the government is keen to reduce the numbers and close down as many as possible. “The collector’s officials have asked us to stop taking new people into the camp. They said they want the camps closed by the end of the month. That seems impossible. People are still coming in everyday, many of whom can no longer stay with their relatives,” says a relief camp organiser in Baroda. However, in a few places like Panchmahal, a sensitive district collector is going about rehabilitation and confidence-building more prudently.

In many villages, camps have not yet been recognised by the government. At Bamanwad village, Panchmahal district, where an arson spree by an outside mob destroyed 27 houses, people are sleeping in the open fields. Unlike in most villages, Muslims here did not flee after the attack. They did not want to leave their meagre land and belongings. In an area where three successive years of drought has impoverished many, local Hindus and people from nearby villages have been providing them food, clothes and support for the last six weeks. “The government refuses to recognise ours as a camp because they say we have already been given a cash dole for a maximum of 15 days. Only seven people, whose houses were burned, have got compensation. It’s very difficult to scrape together some food everyday. Most of us eat only once,” says Ibrahimbhai Khatki, whose house was burned. In the neighbouring village, Nepania, where 140 houses were burned and broken, the relief camp was recognised only on April 15th, six weeks after the attack on the Muslim basti.

Its unclear how the government plans to have elections when even holding board examinations in Ahmedabad and Baroda, scheduled for April 18th, is creating so much fear. Children in relief camps are scared to travel to examination centres in parts of the walled city where the mobs still rule the streets. Three schools in Dilli Darwaja, Ahmedabad were attacked by a mob while students were giving their exams. The police and RAF had to rescue the students. “The violence doesn’t end. The goons behind this know they can get away unpunished. The VHP will continue instigating small incidents until the elections, to keep up the fear and insecurity,” said a police officer. In fact, the VHP had been distributing swords before the violence began and continued to do so weeks after, according to a press report. In rural Gujarat, local Bajrang Dal and VHP activists continue to hold meetings before the attacks.

The police has ensured the criminals immunity from the law. Refugees complain that the police are unwilling to name the main culprits, who are mostly VHP or BJP workers, in the first information reports (FIRs). Moreover, individual complaints are clubbed together into one for an entire village or neighbourhood, so that even if the accused are arrested, it is only once, rather than for each separate FIR. With the criminals still out on the loose, witnesses who have filed FIRs are afraid to return to their homes. In some local reconciliation meetings, local leaders have demanded that refugees should retract names from the FIRs if they want to go back to the village.

Even people advocating peace have been under attack by those interested in keeping trouble brewing. Gandhi’s Sabarmati ashram in Ahmedabad had never seen violence. Not until recently. As NDTV cameraman Pranav Joshi laid injured amongst the Mahatma’s letters and photographs, it became apparent that same Hindutva forces that killed Gandhi were not willing to spare even this haven. A peace meeting at the ashram was disrupted by the BJP youth wing, who protested against the presence of Narmada Bachao Andolan leader Medha Patkar. In the ensuing scuffle, police beat up several journalists, among whom Joshi was badly injured and taken to the intensive care unit. Part of Modi’s fascist plan is also to stifle any voices of dissent, be it the media, activists, judges or unyielding police officers.

Recently, health minister Ashok Bhatt also dashed off a letter spewing venom against three Christian groups that have been active in Gujarat’s peace initiative and foreign aid agency Action Aid. Bhatt said the same groups that discredited the Gujarat’s image during the violence against Christians in the Dangs district in 1998 were doing the same now. He also alleged that these foreign-funded organisations were supporting the terrorists behind the burning of the Sabarmati Express. In the midst of its anti-Muslim madness, the BJP hasn’t forgotten its campaign against the other minorities like Christians.

How much the BJP’s gameplan, of using Hindutva and violence to detract attention from the real issues facing Gujarat, has worked will only be known later. The BJP has failed to deliver on its main election slogan - Na bhay, bhook, bhrashtachar (no fear, hunger or corruption). This summer, more than 2,000 villages in Gujarat are expected to suffer acute water shortages. During the last two summers, hunger deaths and water riots were reported in the drought areas of Saurashtra. “Despite being the most industrialised state, Gujarat has widespread underemployment and informal employment in the state. Ahmedabad has amongst the highest poverty amongst India’s major cities,” says Dr Darshini Mahadevia from the Centre for Environment Planning and Technology in Ahmedabad. Corruption has become institutionalised and has paralysed the government machinery. Voters are also upset with the government’s late relief during the earthquake its attempts to pass on the buck to NGOs for rehabilitation of the Kutch earthquake victims.

In fact, Narendra Modi was brought in to replace Keshubhai Patel as chief minister in October 2001 because the party sensed the growing public anger against its government. Modi, an RSS hardliner who had never stood for election before, was brought in to organise the cadre for the 2003 elections. He took over after the BJP lost two assembly by-elections, one in Sabarmati, which falls under Union home minister L.K. Advani’s Lok Sabha constituency. The first signs of the BJPs declining popularity were evident during the September 2000 district panchayat elections in which the BJP lost 23 of the 25 district panchayats and the majority of taluka panchayats. Earlier, it controlled 24 district panchayats. In the municipal elections in 2000, the party lost two crucial municipal corporations - Ahmedabad and Rajkot, which it had ruled for 13 and 24 years respectively.

Modi has tried reviving the party’s flagging popularity using a militant Hindutva line. He is attempting to implement the party’s fascist plan in the BJP’s Hindutva laboratory, the only state in which the party has a clear majority, with 117 of 182 assembly seats. In fact, less than a month after the violence in Gujarat began, BJP district committees were asked to assess their chances of victory if a mid-term poll were announced. Elections are scheduled next year. The pattern of the recent violence also reveals that certain Congress strongholds in north and central Gujarat, like the tribal Panchmahals and Sabarkantha districts, were the ones targeted by VHP mobs.

The continuing violence seems to be laying the ground for the big fight ahead. It’s time for free and unfair elections in India’s Wild West.

Frontline, Apr. 27 - May 12, 2002 Also available here

No comments:

Post a Comment