If you want to stay alive, run to the graveyard

Overnight, thousands were made homeless during the Gujarat massacres. Their only refuge were dargahs, schools, and even graveyards.

DIONNE BUNSHA

When Fatima (name changed) went to celebrate Eid at her mother’s house in Randhikpur village, Patan district, she never imagined she would finally land up being a refugee in a relief camp in Godhra, her family and her life totally destroyed. After their houses were burned by a mob in the village, Fatima fled with a group of 35 people. “We didn’t know where to go. For three days, we walked from village to village asking for protection. We stayed one night in a masjid, another in adivasi houses. By then, our number had dwindled to nine women,” says Fatima.

As they walked to the next village in search of shelter, they were ambushed by a group of powerful men from their village, most of whom Fatima can identify. They stopped their cars, gang raped the women and killed them all -- except Fatima. After gaining consciousness, Fatima lay on the road for almost 24 hours, pretending to be dead. She was finally rescued by the police and taken to a school in Godhra where Muslim charities are running a relief camp.

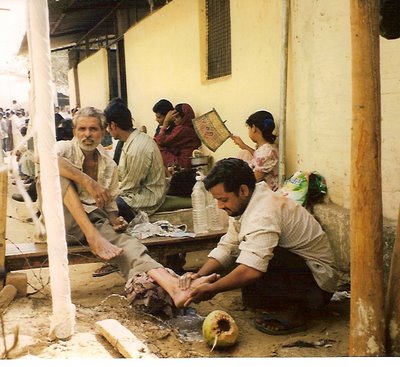

Packed with people, relief camps have emerged as the only shelter for the thousands who have fled their neighbourhoods. However, the journey both to and out of the camps prove most difficult for riot affected people. In rural Gujarat, many people fled their homes and hid in the hills or jungles for days without food or water before finally being rescued by the police. “There wasn’t even water there. We ate leaves,” said Sapura Ghachi, who hid with her husband and daughter on a hill for three days before her husband was taken to Godhra general hospital for treatment. Since the camps are situated in towns very far from villages, hardly anyone knows about them. Moreover, most camps are so far, people can’t reach them unless the police escort them here.

Camps situated in Ahmedabad’s slums are far more accessible. People fleeing their homes have run to the local masjids or schools nearby. However, the conditions here are far more cramped due to the space shortage in slums. Hundreds of people are packed in a small school or tent. At Pir Kasamshak ki Roza in Ahmedabad’s Gomatipura area, people are actually living inside a graveyard. Better to be on a graveyard than under it, is probably what most refugees here have figured. “We have no other security. When bullets start flying, we rush here. There was a camp set up here during the 1985, 1990 and 1992 riots as well,” says Munni Bibi Rasul, whose son was killed in police firing.

Only Muslim charities have set up camps, by pooling contributions from within the community. Neither the government nor non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have taken the initiative. The state government announced compensation of Rs one lakh to the families of those killed in riots, as compared to Rs two lakh for the families of those killed in the Sabarmati Express attack, a telling statement on the ruling party’s prejudices. The morsels of relief that government is handing out was also delayed. One week after the violence began, the collector’s offices started supplying provisions to the camps.

The flurry of sympathy, aid and NGOs that rushed to Kutch after the earthquake last year is missing when it comes to riot victims. Many executives of large NGOs, prominent in earthquake relief, chose to remain confined within the safety of their homes even a week after the violence when curfew was lifted in Ahmedabad. A group of 20 NGOs in Ahmedabad, called Citizen’s Initiative, were quick to start co-ordinating help and supplies. But that is all it remains confined to. Even their volunteers were initially threatened by local goons to stop supplies. “Its more difficult to work in this situation as compared to the earthquake. This was a planned ethnic cleansing. There are people who want to make sure help doesn’t reach,” says one of the volunteers. Moreover, the stakes aren’t high enough. Foreign aid isn’t being shoved down our throats the way it was during the earthquake.

In fact, Muslim charities, which managed to mobilise resources during riots, are finding it difficult to raise funds this time since even middle class Muslims have been economically destroyed. They are somehow able to provide basic services in camps. The NGOs co-ordination group has just started mobilising nursing and counselling services. The level of sensitisation to such issues, especially in rural Gujarat, is evident in Fatima’s case. She was prompted to speak about her gang rape to press reporters while a room full of strange men listened. It was only when the men were asked to leave, that she felt more comfortable to speak. Moreover, she was made to narrate her horrific story twice or thrice a day, depending on how many visitors came.

While medical facilities are basic - confined to check-ups by volunteer doctors and nurses, refugees are afraid to be taken for treatment to the hospitals. “Many pregnant women are expected to conceive soon, but they refuse to go to the hospital. They insist on delivering the baby in the camp itself,” says Fr. Victor Moses, who is co-ordinating the Citizen’s Initiative. He is also concerned about hygiene conditions at the camps. With around a few toilets being shared by 800 to 900 people, sanitation is impossible to maintain.

In one camp, security is a problem. Witnesses who spotted prominent leaders in the mob are now being targeted. The Sangh Parivar, which was blatantly aggressive in the first few days of violence, is now realising that the law still exists and have hired a legal team to defend their activists. Ironically enough, the law enforcers have also been scared to escort trucks into the relief camps. “People are angry with us. They feel that we have been part of the attacks on them. They could do anything when we enter the area,” says a policeman who was part of the escort team. Adds a relief volunteer, “When we are on the streets, transporting supplies, they protect us. But when we are in the relief camps, the police keep asking us to make sure they are safe.”

While refugees are still too scared to venture beyond the camps, although desperate to know if their shops have been burned, many dare not risk their lives. Yet, life in the rest of Ahmedabad goes on. With curfew lifted, the streets are buzzing with traffic. Normal life slowly returns to the city, although several businesses have been destroyed. But for the refugees, life is far from normal.

Long-term rehabilitation is still a big question mark, which no one knows how to grapple with. Left with nothing except the clothes on their back, it remains uncertain how the 60,000-odd refugees in Ahmedabad’s relief camps and the thousands of others stranded in rural camps will start their life from scratch again.

Frontline Mar. 16 - 29, 2002 Also available here

No comments:

Post a Comment