After the bullets, the ballot

Chief Minister Narendra Modi is a man in a hurry—to cash in on the hate at the hustings. Will it pay?

DIONNE BUNSHA

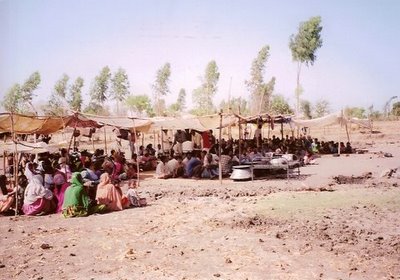

It was politics that incited a mob to loot and burn her house. But politics is the last thing on Asiabibi Sayeed Ansari’s mind. Still living in the Bakar Shah Roja relief camp in Ahmedabad, Asiabibi is not even certain where her next meal will come from. The government has de-listed and stopped supplies to the camp she stays in, although it houses around 650 people. On July 20th, the camp organisers said they would not be able to cook for the refugees anymore. “They gave us rations and told us to prepare our own food. But we don’t even have vessels to cook in,” says Asiabibi. Her house is being re-constructed by a Muslim charity. “The government gave us only Rs 2,000. That will not even pay for the door,” she says. “They should first make sure that everyone has got back their homes and jobs, then think about elections,” Asiabibi adds.

But chief minister Narendra Modi isn’t bothered about Asiabibi or the estimated 25,000 refugees in Gujarat’s relief camps. His only priority is to hold elections as soon as possible, to count his votes over their losses. Over 1,000 people were killed in the state-supported communal violence and more than 1.5 lakh people were made homeless. Eager to cashing in on what he perceives to be a ‘pro-Hindutva’ wave (but others call ‘fear’ and ‘terror’), Mr Modi dissolved the Gujarat assembly on July 19th, immediately after the presidential elections. He asked for early polls, much before the scheduled elections in early 2003. This led to chaos in Parliament. Both Houses of Parliament were adjourned on July 22nd with the opposition protesting against Modi’s move. They called for his dismissal and for President’s rule in the state. But the BJP was in no mood to listen. Deputy prime minister L.K. Advani said Modi had handled the riots better than any other chief minister in the last 50 years.

Photo: Dibyangshu Sarkar/AFP

Despite Modi’s blustering confidence, it may not be an easy ride for the BJP. The Hindutva chariot could get stuck in the mud. A great deal depends on how much support Modi is able to garner within his own party. His egoistic and authoritarian style of functioning has rubbed several senior leaders and ministers the wrong way. Some were against the manner in which he handled the post-Godhra violence. They feel that the situation should have been brought under control much sooner. Several Hindu families and businesses also suffered as a result of the prolonged violence. Many local BJP activists were also arrested, upsetting their local support bases.

Since Modi has no mass base, his fate is closely linked to the support of his predecessor Keshubhai Patel. Until now, Keshubhai has been keeping a low profile. Recently, he was offered the post of party president but declined to accept it. With a strong base in Saurashtra, where the BJP has 51 of the 58 assembly seats, he is one of the most powerful Patel leaders. Patels are one of the two dominant castes in Gujarat politics, comprising 20 per cent of the population. They have been the BJP’s strongest allies. The other dominant caste is the Kshatriyas, which also accounts for around 20 per cent of the population. They have traditionally supported the Congress. The KHAM (Kshatriya, Harijan, Adivasi, Muslim) formula has been the Congress’ strategy in Gujarat for more than a decade. But its influence within these sections has been under threat, with the BJP trying to mobilise tribals and dalits to participate in the 1992 Ram Janmabhoomi Yatra.

Just a day before the Gujarat assembly was dissolved, the Congress jolted itself from slumber. Shankarsinh Vaghela, a powerful Kshatriya leader, was appointed Gujarat Pradesh Congress Committee president. A former BJP stalwart and RSS pracharak, Vaghela rebelled against the BJP in 1995, when his rival Keshubhai Patel was made chief minister. Vaghela’s entry has changed Gujarat’s political atmosphere in several ways. It has revived hopes within the Congress, which is considered a weak opposition party. Vaghela is backed not only by the Kshatriyas, but also by the Hindu Other Backward Castes (OBCs), who comprise around 40 per cent of the population. He had mobilised OBC support for the BJP. Vaghela is also very influential with the Gujarati media and a few powerful industrial houses like Reliance and Gujarat Torrent. He is seen as someone who can give Modi a run for his money, since he knows the inner workings of the BJP. Moreover, Modi and Vaghela worked together as general secretary and president of the Gujarat BJP respectively from 1985 to 1990. Now they will clash as chief ministerial candidates in the coming elections.

While the BJP is likely to use the communal card, Vaghela will play caste politics. Known as a crafty manipulator, he is also capable of engineering cunning manoeuvres. After Keshubhai became CM in 1995, Vaghela engineered a split in the BJP and horse-traded MLAs to form his own party, the Rashtriya Janata Party (RJP). At that time, he airlifted defecting MLAs to a secret destination in Khajuraho to keep them away from the influence of the BJP. There have been no defections at the start of this current battle. Vaghela is using the BJP’s involvement in the violence against them. His election slogan is ‘Riot Free Gujarat’.

Voter anger against the BJP government has been so vociferous that despite its weak organisational strength, the Congress has won all elections held in the last two years. In recent municipality elections for president and vice president held in early July, the Congress wrested power from the BJP in Anand, Khambhat and Borsad and re-established its hold in Petlad. During the district panchayat elections, held in September 2000, the BJP lost 23 of the 25 district panchayats and the majority of taluka panchayats. Earlier, it held control over 24 district panchayats. In the municipal elections held at the same time, the party lost two crucial municipal corporations - Ahmedabad and Rajkot, which it had ruled for 13 and 24 years respectively. The BJP retained control over the other four municipal corporations, but its victory margins were heavily reduced. But, the BJP still has 117 of the 182 state assembly seats. However, insiders feel it may not be easy to retain these seats, especially if Keshubhai does not co-operate with Modi. During the last assembly elections in 1998, it was a triangular fight between the BJP, Congress and RJP. The anti-BJP votes were split between RJP and Congress. Many BJP candidates won by a narrow margin because of this split, party sources say.

The ‘Hindu vote’ that the BJP is eager to cash in on also seems to be somewhat nebulous, considering that there is no heterogeneous Hindu society. Caste is more likely to dominate voting patterns, with the two most powerful castes - Patels and Kshatriyas - pitted against each other. The Congress is also hoping that public anger against the non-performing BJP government will override the Hindutva wave, especially in places affected by communal violence. The BJP anticipates that the fear generated will reap profits for them mainly in urban areas and parts of central and eastern Gujarat, where the Sangh Parivar unleashed its communal fury. Several parts of the state like Kutch, Saurashtra, south Gujarat and parts of western Gujarat remained peaceful. Here, the more pressing survival issues relating to drought, employment and water shortages are likely to dominate.

The BJP’s bungling in governance and the economic recession are likely to be most important in voter’s minds, although the carnage of the last five months was an attempt to divert attention away from it. The state’s finances are in shambles with the deficit valued at Rs 363.95 crore. In addition to this, much higher debts are mounting. Over the past five years, the BJP has transformed a surplus budget into a negative one. Development work has ground to a halt with contractors bills worth around Rs 1,000 crore unpaid. Contractors held a morcha in Gandhinagar recently, demanding payment. The state also faces a power crunch, with a shortfall of around 20 per cent. Residents of Kutch and Saurashtra are bitter about the large-scale corruption involved in earthquake rehabilitation. The government took loans worth 900 million USD from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank for rehabilitation. But ground realities do not reflect even a tiny fraction of the money spent. Gujarat is also facing a severe water crisis. In summer, more than 2,000 villages in Gujarat had acute water shortages. Around 80 per cent of the state’s water resources are in the industrial south Gujarat region. But the water is polluted with industrial toxins. In north Gujarat, excessive drilling of borewells has also resulted in water contamination.

Even before the economy was ruined by the communal carnage, the state had already slipped into a recession. “While Modi keeps boasting about foreign direct investment and large companies like Reliance investing here, the state’s own industrial base is in shambles. Small and medium industry, which laid the foundation for Gujarat’s progress is in shambles, with around 60 per cent either sick or closed,” says an industrialist. “Moreover, the state corporations which gave the impetus to the state’s industrial progress by providing support to industry are also on the verge of closure.” These include Gujarat State Finance Corporation, Gujarat Industrial Investment Corporation, Gujarat Small Industries Corporation and Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation. It is estimated that around five lakh workers have directly lost their jobs due to the closure of small scale units alone. Besides these, many others in allied industries have also suffered job losses. The communal carnage has made matters worse for Gujarat’s economy, destroying several small businesses, shops and cafes. Besides, several other businesses have suffered crippling losses due to closures during months of curfew. The situation is so bad that four families in Ahmedabad committed suicide in July after facing financial ruin.

Modi’s pretending that all these tragedies don’t exist will not make the hard realities in Gujarat disappear. His government even denies that people like Asiabibi exist. Their camp is has been scratched off government records. They remain displaced in their own homeland. The next few months will tell whether Modi’s blinkered and bloody-minded saffron approach to the polls will also make the BJP’s votes vanish.

Frontline, August 3 - 16, 2002 Also available here